Moving Up and Beyond Maslow’s Pyramid

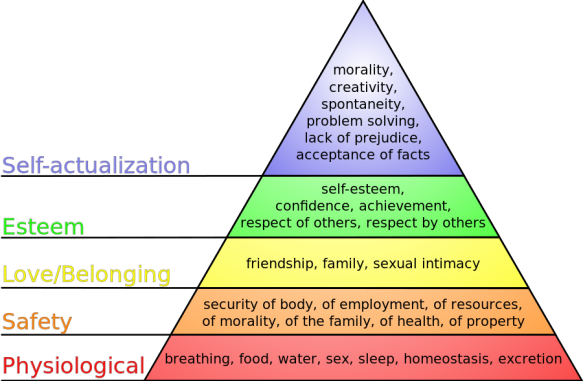

In his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,” American psychologist Abraham Maslow outlined a hierarchal structure for what motivates human behavior. Though many have greatly expanded his theory, it has remained popular because of its intuitive logic. Here’s how how he framed human motivation:

- Most important is physiological needs: food, water, protection from the elements.

- Second most important need is safety: once we feel somewhat confident that we will eat and sleep undisturbed for the day, we make sure that we can do the same thing tomorrow, ensuring the safety of resources, food, employment, etc.

- Third most important need is belonging and loving.

- Fourth most important need is esteem; this can either be what Maslow called “lower” esteem, which is gaining esteem through external means or “higher” esteem which is internally generated.

- The top of the pyramid is the need for self-actualization, which encompasses the human capacity to live to his or her fullest potential and have higher purpose.

Within Maslow’s theory, if a lower need is not satisfied, it’s tough to think about a higher one. If we can’t secure clean drinking water (physiology), we’re probably not going to be thinking about artistic expression (self-actualization), and so on.

In many ways, our consumer culture–and the marketing that drives it–uses Maslow’s theory to get people to buy stuff they don’t necessarily need. Noted evolutionary psychologist Gad Saad said this in his 2007 book “The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption” about the intersection of Maslow, consumer behavior and marketing:

A perusal through leading consumer behavior textbooks reveals that the most ubiquitous theory to address this issue is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs….Consumer motives are mapped onto one of the five hierarchical levels, as are the consumer products and services that cater to those needs. By joining the American military, one is addressing one’s self-actualization needs (i.e., “Be all that you can be”). Similarly, by engaging in conspicuous consumption of fashion items, one is meeting his or her belongingness and possibly esteem needs.

But Saad explains that Maslow was a bit facile in his logic. Saad believes that some of our higher needs can seem just as important as lower ones from an evolutionary psychological perspective:

Maslow’s hierarchy assumes a strict hierarchical ordering of needs, goals, and motives. In other words, the theory proposes that higher level needs are pursued, only after lower level ones have been met. Van Kempen (2003, see pp. 165–167) proposes that this could not be a veridical theory because it cannot explain why the poor spend money on status products when they are deprived of their most basic needs. An evolutionary account recognizes that seeking status is a Darwinian drive that can at times be as important and primordial as many of the other first-level needs identified by Maslow.

In other words, bracketed inside Maslow’s logic, people driven by aspirational marketing will ignore their lower needs to secure their higher needs. E.g. someone might miss a rent payment (safety) to pay for a handbag that will earn her the esteem of her peers.

Whether inside of Maslow’s easy-to-digest, albeit flawed pyramidal structure, or Saad’s more nuanced Darwinian model, it’s fairly easy to see that we are often prodded to buy stuff–whether it’s a tube of toothpaste or a luxury car–because of a promise that these things will satisfy some very basic, perhaps primordial, need.

But do these things work? Has anyone ever said they met the love of her life because of a particular brand of toothpastes? Has anyone ever said (truthfully) that his esteem was permanently elevated because of a new car?

What if we stripped away the marketing double-speak and saw stuff for what it was? What if toothpaste was just something to clean our teeth, not something that would help us find true love? What if a luxury car was just something to get us comfortably and quickly from point A to B, not something that proves we made it in the world? What if stuff was just stuff, sometimes useful for living, but rarely–if ever–a tool for satisfying our highest needs? How would we live if this were the case? What would we wear? What would we drive? What would we live without?