It’s Your House on a Bike

We feature a number of homes that sit on internal combustion vehicles. Despite what you might think, these homes can be extremely green. First off, standard homes have fuel needs too, from heating hot water heaters to keeping stoves alight to keeping furnaces firing. Stationary homes consume gas, just not for locomotion. More importantly, there’s a dire need for efficiency when you’re moving your home around; everything that isn’t totally needed, whether it’s water for showering or an extra pair of pants, is sacrificed due to very limited space and keeping weight down so your vehicle can keep moving.

But if you’re like me (and I shouldn’t suspect, or hope, that you are) there’s the dream of the nomadic home that doesn’t rely on fossil fuels. In the past, we’ve looked at the Tricycle House as well as the Taku Tanku house–both were bicycle-powered housing options (the former somewhat plausible in its execution, the other not). We can now add a couple more HPNMs (human powered nomadic home…you heard it here first) to the mix.

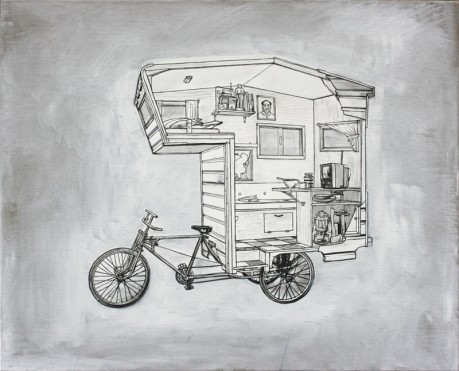

The first is the Camper Bike by artist Kevin Cyr, which resembles a 70s over-cab pickup truck camper. While there are no detailed images of the inside, a sketch shows the over cab portion containing a bed (for a medium sized cat, it appears), a dining table, a TV, some storage and a picture of Mao.

In an interview on Icebike.org, Cyr explains the project:

The idea first came to me while I working in Beijing. I was joking with a friend that the only thing not on the back of bikes in China are houses. I had been seeing people, mostly working class men hauling goods on three wheeled bikes—rickshaws with bamboo flat beds. They were carrying huge loads of foam and plastic for recycling, furniture, and building materials. There were also a lot of food venders at open markets cooking meals on the backs of these bikes, it was very interesting. They seemed to use them in every way imaginable much in the way Americans use pick-up trucks.

He built the Camper Bike, which he describes as a sculpture, over the course of three trips over three years.

Cyr made few concessions to practicality. He used an old, rickety government issue bike as the camper’s host vehicle. The camper is mounted on a wood frame, which is significantly heavier than an aluminum or composite one–Cyr suspects the whole thing weighs a very portly 200 kgs (440 lbs). Cyr said when he climbs up to the bed area, the camper sways and feels as though it’ll fall over. He says if he were to make it again, that’d he rectify these design flaws.

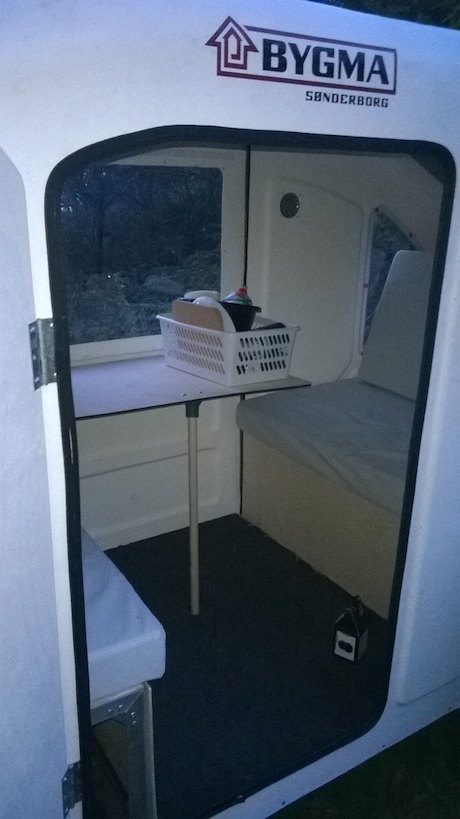

Rectification of those issues is what Dane Mads Johansen has done with his Wide Path Camper (Johansen said he was inspired by Cyr’s project). Unlike the Camper Bike, the WPC is a trailer, so you can choose which bike you want to affix it to. It also uses lightweight materials keeping weight down to a very reasonable 45 kgs (100 lbs). The camper, which has two sections that nest on top of each other when being towed, features a seating area that converts to a bed and offers around 11 cubic feet of storage (a little less than the trunk of a Honda Civic).

Unlike every other bike-camper we’ve seen, the WPC is not vaporware. Johansen is taking pre-orders and expects to start delivering next month. The basic camper sells for €2000 ($2200 USD) and there are a number of available upgrades like a €600 solar package.

Some of you might be thinking, “Why not just load panniers or a trailer with camping gear, achieve the same result as the camper and save money and weight.” This is a nice idea, but belies the hard truths of bike touring, which often includes inclement weather and a deep desire for comfort at the end of a long day of biking (I’ve bike toured the world extensively including riding 1.5 times across US, so I feel I can speak on the matter with some authority).

At 100 lbs without gear, the WPC is still pretty heavy (my cross-country rig weighed a little over 50 lbs with full camping gear), so I think its best application is limited geography tours or a quasi-living situations–i.e. setting up at a campground or in someone’s yard where there’s access to a toilet and running water. However you use it, it’s a very cool piece of gear.

Many thanks to Mads for the tips!